The notion of self-care is vague – it appears to encompass anything which makes you feel good. Yet true self-care intentionally subverts the capitalist expectation that we have to be constantly producing in order to be worthwhile. It is unsurprising that self-care has seen a rise in popularity in recent years, considering the predominance of the online gig economy and its #riseandgrind culture. If you have to constantly pursue working opportunities in order to survive, and if all the while this barrage of work is available at your fingertips 24/7, rendering the line between work and non-work increasingly blurry, then finding ways to release is revolutionary. This notion of stopping, relaxing, and refusing to be “productive” has, like all good things, become commercialised. You aren’t doing self-care right (or so targeted ads would have you believe) unless you purchase this app that tells you how to breathe, or this candle, or this body butter. I am not against apps, or candles, or body butter, but for capitalist structures to survive, it requires both production and consumption. If practising self-care is the rejection of the constant need to produce, capitalism has a vested interest in turning the practice into consumption. This commercialisation has distorted its revolutionary roots, but at its most basic, self-care is a subversive act.

In the epilogue of her essay A Burst of Light, writer and activist Audre Lorde wrote: “Caring for myself is not self-indulgence it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare”. As a black, queer woman, the power structures of patriarchal, white supremacist capitalism in which we live were fundamentally against Lorde’s existence. Just to exist as a black queer woman is to subvert power structures, never mind also dedicating one’s life to actively fighting against them. To then surrender to care and relaxation was therefore a radical notion. The Nap Ministry, a project that facilitates “immersive workshops and curate[s] performance art that examines rest as a radical tool for community healing” especially for Black Americans, is a perfect example of this revolutionary self-care. In a world that has over-worked and underpaid black people, providing space for unapologetic rest is essential radical activism.

This form of self-care is defined by a withholding from action; it is about not doing things (as defined by the capitalist meaning of “doing things”, since taken literally even resting is still doing something). Rest is a form of activism when it is practised by those oppressed by capitalism, in all its patriarchal, white supremacist villainy. Thus, it can be subversive when practised by nearly everyone. However, acknowledging our differing levels of privilege, and the responsibility which accompany that, must be recognised alongside the practise of restful self-care. I believe that upholding these responsibilities can be a form of self-care too. This type of self-care is defined not by an intentional lack of doing, but by intentionally doing.

In my third year of university I experienced a depressive episode that rendered me near-suicidal. To me the world seemed a terrible place, full of pain and injustice, in the face of which I felt powerless. My immediate response to this was to stop engaging with it, to stop reading the news and to stop thinking about it. I was driven back to my childhood home by my sister to spend some time with my dad. This decision in itself is dripping with privilege, and yet I believe doing so probably saved my life, and after all a dead Nancy can help no one while a living one can at least try. Self-care as abstention from action was necessary. Yet, to continue to abstain from engagement in the world would not have been self-care, both because it would not have remained true to the essentially subversive nature of self-care, and because it would have been detrimental to my health and happiness. While sometimes caring for yourself requires momentarily running away, ultimately, we require fulfilment for happiness, which requires engagement.

The idea that engagement is self-care is ancient. It was taught by Socrates when he dedicated his life to educating others, both because he wanted to better others, and because it was good for him, a subversive act that resulted in his execution. It is also taught in Eastern religions, like Buddhism, which does not only teach meditation, but also the power of service and kindness, each bringing you closer to enlightenment. But then Christianity re-engineered charity into currency to buy our way into heaven, and colonised most of the world, stamping out this balance of care in dominant Western culture. Descartes then wrote “I think therefore I am”, and Nietzsche proclaimed that “god is dead”, and we were left entirely separate, with no higher reason to help others. Combine this with the atomism of the Enlightenment, and social Darwinism arising out of the theory of evolution and suddenly the capitalist notion that everyone is out for themselves created a partition between “selfish” and “selfless”. If we define self-care as indulging unapologetically in activities which are good for me, it is easy to see how acts which help others can appear not to be within its remit. Yet, when we realise that the separation of selfishness and selflessness doesn’t make sense, we can see how both are essential to self-care.

Ultimately what made me able to battle out of depression and control my feelings of powerlessness, was by acknowledging that I had a responsibility to make changes in the world. By acknowledging my responsibility, I was also acknowledging my power. Then, in 2018, when I developed M.E. that made me unable to work, and I was stripped away from the capitalist cycle. I could not contribute to productivity and I was plunged into a world where my entire life was self-care. Everything I did was in order to make myself feel better, to take my time, to rest, to relax, to minimise pain. It was during this time that my already burning anger towards social injustice swelled, and the small ways in which I was able to fight against that injustice became a self-soothing synonymous in my experience to meditation or taking a really long bath. The self-loathing Nancy of my times of deep depression would have felt guilty – if helping people makes me feel good, is it really care? But now, the boundaries of selfish and selfless melted away, and I knew that what was good for me was good for the world, and what was good for the world was good for me. And surely, a person who feels good when helping others is a good person?

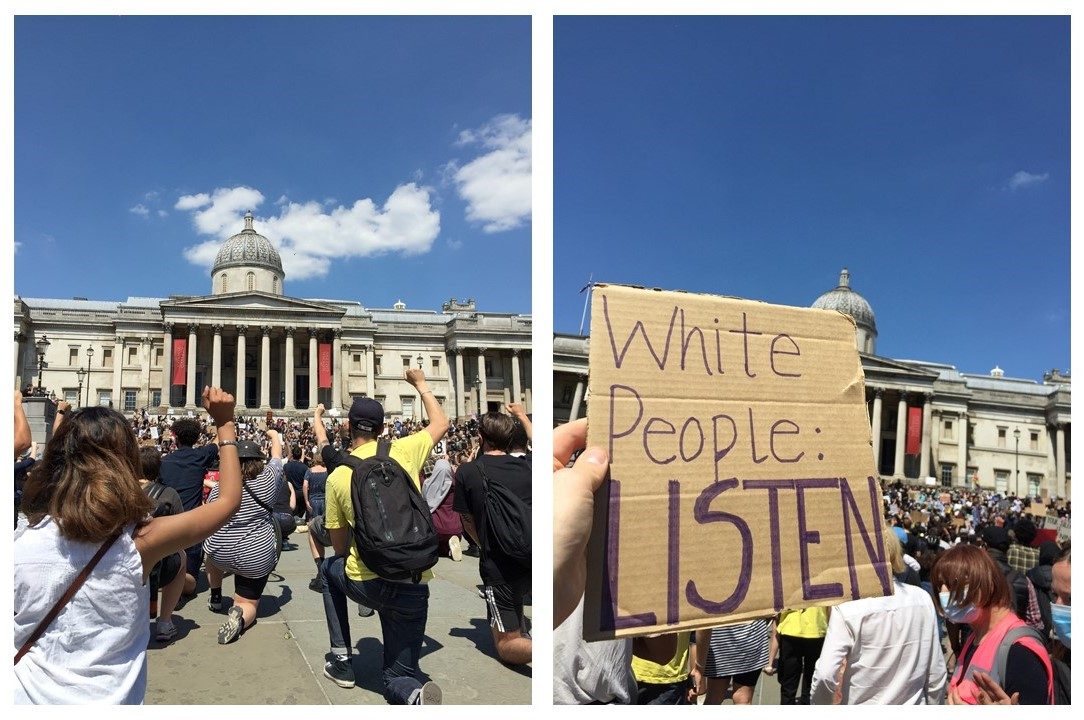

Engaging in activism takes many forms – for me, especially as I am often not as capable of physical involvement such as protests and community volunteering, it looks like putting my money where my mouth is. I am privileged, I have enough money to give to others, so I have a responsibility to do so. I give money to organisations and I to individuals. Want to support the trans community? Donate to Mermaids, but also donate to crowdfund a trans person’s surgery. Charities and non-profits can be great, yet often it takes a lot of research to really figure out the good ones. With financial direct action, you can ensure those receiving your money really are the ones who need it. Of course, many of us cannot afford to donate regularly to multiple causes, I can’t donate to every cause because I wouldn’t be able to eat, but there are many ways to support these causes for free: write to your MP, write to the government, sign petitions, create petitions, share crowdfunds and Just Giving pages, share causes to raise awareness about them. People can’t support causes that they are unaware of, so make them aware. Above all live by your convictions – the most radical act of self-care for me was realising that every time I did not speak up when those around me engaged in behaviour I knew to be unjust, I felt more and more diminished. Self-care is calling out your friends.

Activism is acknowledging that you have power, that you are someone, that you exist and that you make a difference. Activism is living by your beliefs and taking responsibility for yourself. Activism takes into account your thresholds, it doesn’t ask that you walk in protests if you are physically unable. As the educator, Rachel Cargile, recently wrote “Activism is not synonymous with overworked and underpaid”. Activism doesn’t ask that you sacrifice yourself for others, but that you acknowledge how helping others helps you. Activism is self-care, for the same reason self-care (in its traditional sense) is activism – because both subvert the oppressive systems under which we all live. Ultimately, the most caring thing I can do for myself is the same as the most caring thing I can do for anyone else: resist the patriarchy, fight white supremacy, subvert capitalism.