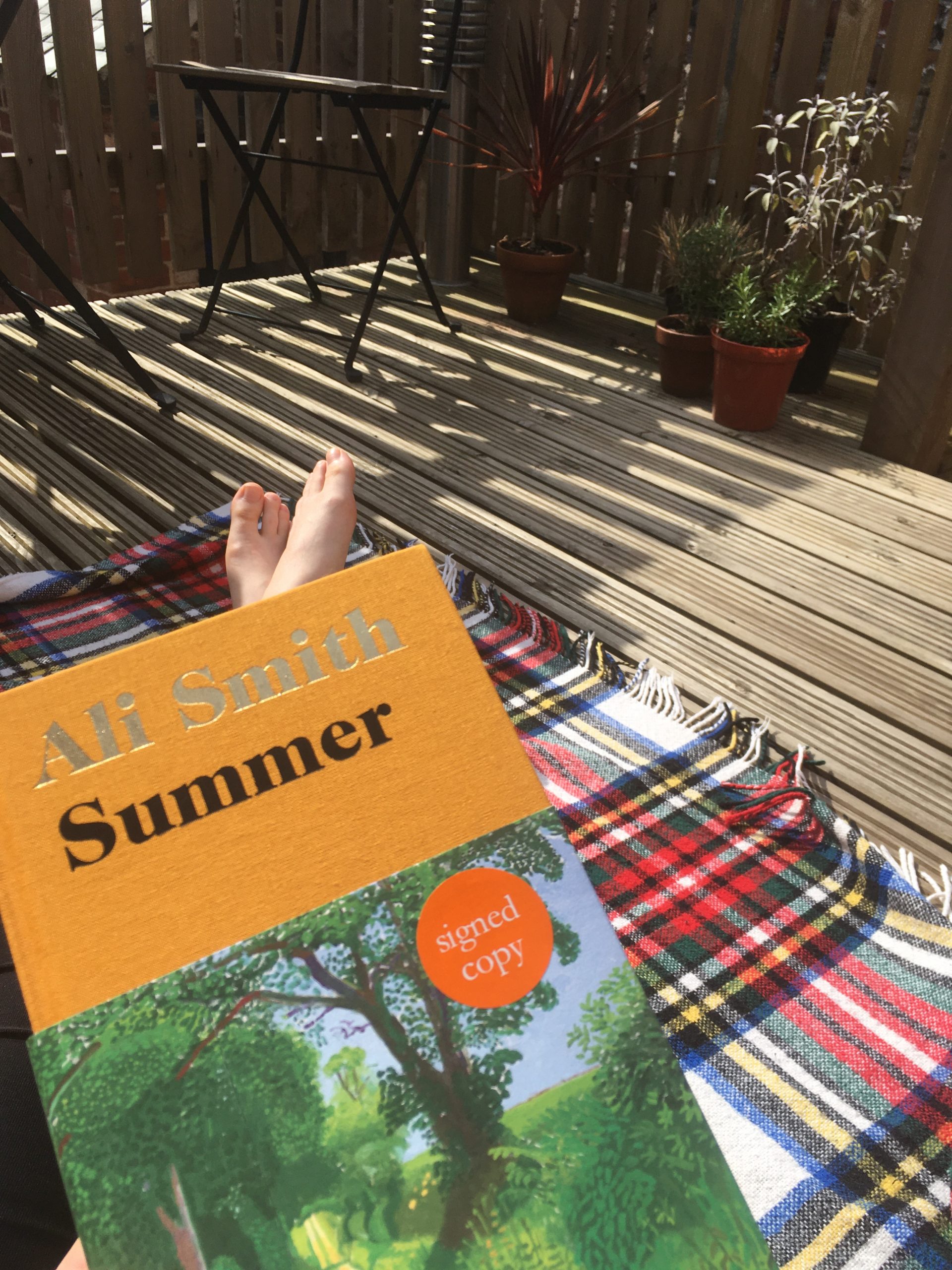

I always think spring is my favourite season until its colour drenched blooms give way to the warmth of the summer sun kissing my skin. So, I decide I must love summer the most, until the branches begin to bend with the weight of their fruit, and the trees are crowned with gold. The crisp air of autumn clears my lungs, and I lament its passing as we head into the dark months of winter. Yet, I cannot deny the beauty in that muffled silence of a street blanketed in snow, or the twinkle of lights from a stranger’s windows. I read each of Ali’s Smith’s seasonal quartet in the season they correspond with; each season of a year punctuated by these books that I relished. The turning of the season meant not only new colours and new light, but a new instalment of this series. I cried when I finished, sat in my garden in that August heatwave that burned the tip of my nose, and wished that there were more seasons in the year.

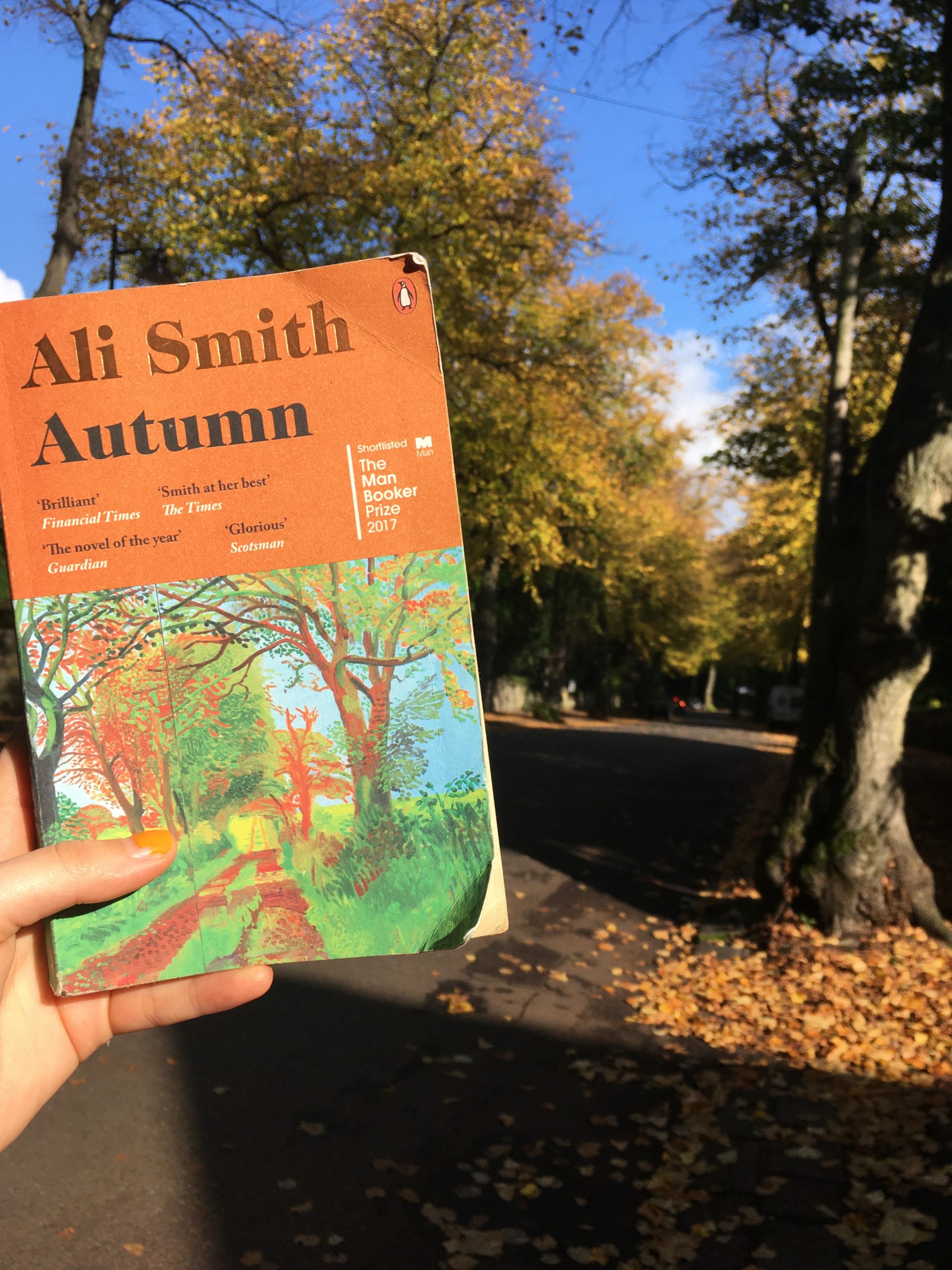

I had found a battered copy of Autumn in a charity book-shop. Inscribed on the first page was a note:

Here’s one to savour.

Enjoy – slowly.

“We have to hope, Daniel was saying, that the people who love us and who know us a little bit will in the end have seen us truly. In the end, not much else matters” p.160

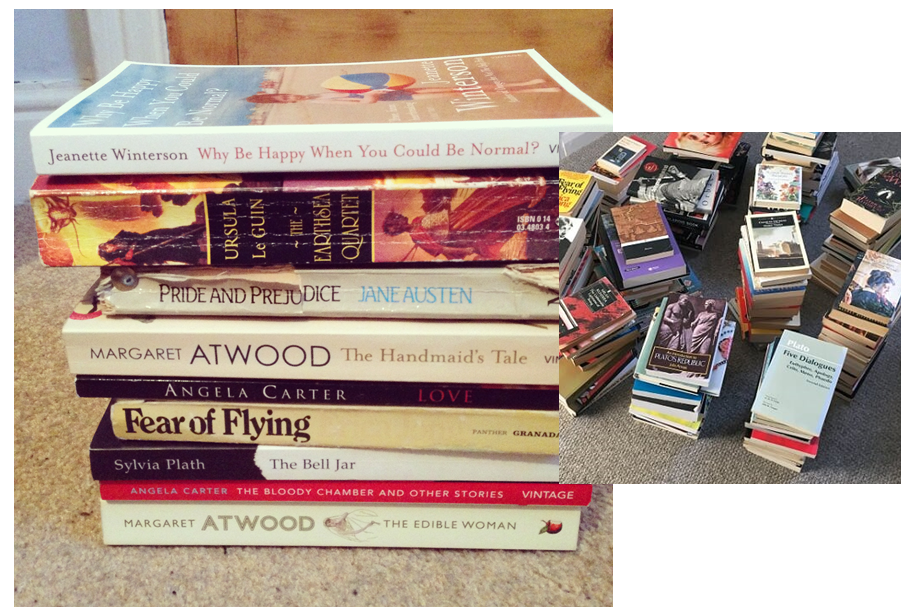

For a book that starts with the bastardised Charles Dickens quote “It was the worst of times, it was the worst of times”, Autumn is surprisingly spattered with these moments of hope. Written in 2016, right after the Brexit referendum, the book is often described as a “Brexit novel”, yet the political divide is not at its centre. Instead, Brexit forms the backdrop behind the actions of the novel’s players. Like our own lives throughout the referendum and its fruitions, it is constantly present in the background. There is a sense of fear and confusion, and of baited breath; a country in suspension, waiting for the leaves to fall and the darkness to fall with them. Elisabeth reads Brave New World aloud to her dying elderly neighbour, placing the image of dystopia in our minds, without ever outright asking the question “are dystopias any worse, or just different?”. Yet Autumn is not full of only misery, but beauty too. Beginning outside of reality in a dreamlike state, before plunging us back into the here and now, Smith shows us that time, and our place within it, is as transient as the seasons themselves. Within this transience, the presence of art and its profound and permanent effect on those who experience it is integral. Art brings hope, comfort, and some form of permanence. Aldous Huxley existed through time with Brave New World, and the works of Pauline Boty changed Daniel’s life, and through him Elizabeth. Art can change the world, even if those changes seem imperceptible; kindness too, and friendship, and the things shared between friends. The Platonic (both in the sense that it was never inappropriate, and that their conversations replicate Socratic form) relationship between the elderly Daniel and his young neighbour Elisabeth shows that ideas, art, friendship and conversation alter our lives, and thus the world.

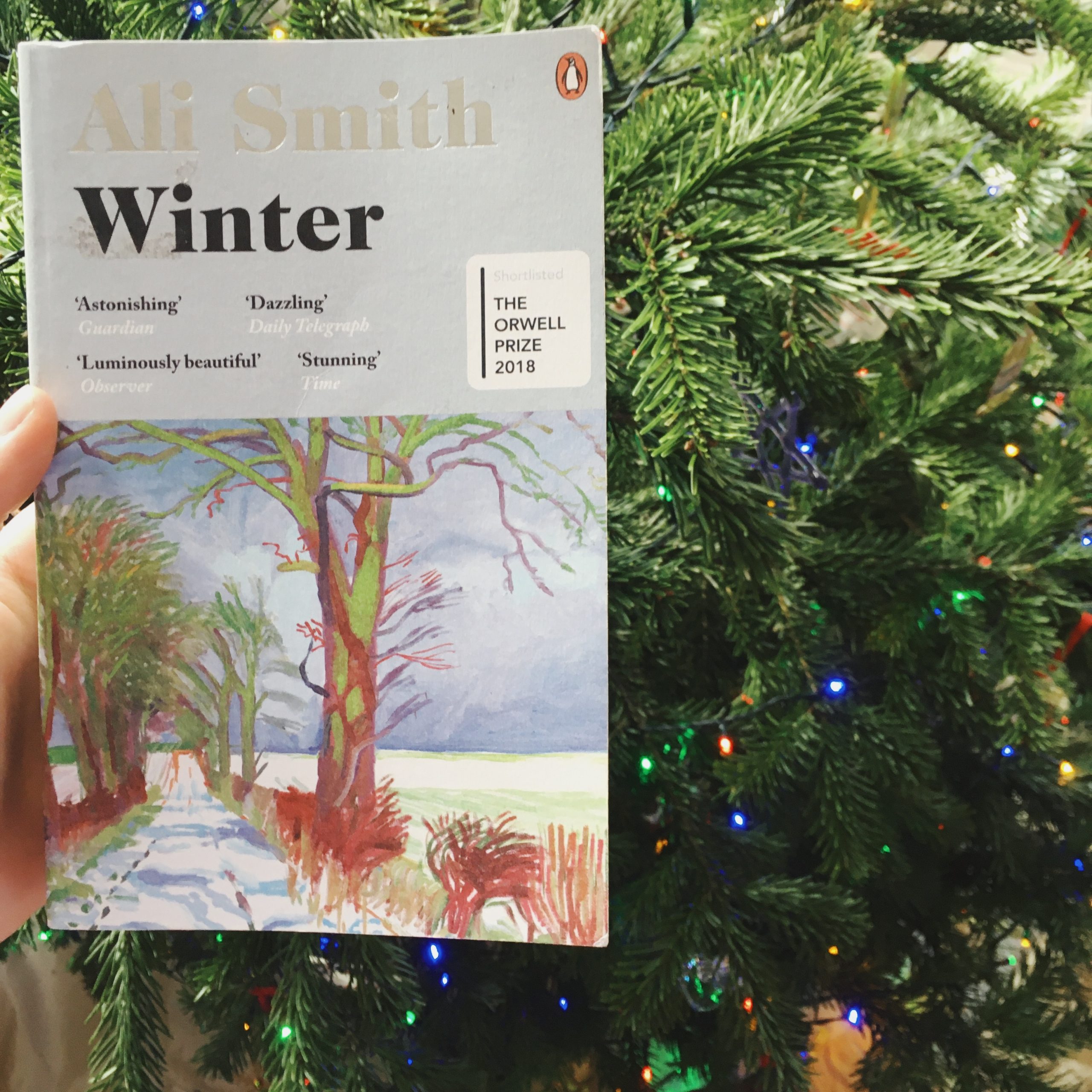

Like the season itself, I struggled a little through Winter. I found its stark bleakness tough after the rich red and gold of Autumn. More Dickensian than ever, Winter begins with isolation, loneliness, and almost ghostly apparitions. The stories of a lonely old lady with a hallucination, a failed relationship and family estrangements set the cold and empty scene. Yet, once more, we find hope in friendship and family, in the rallying of strangers and in Christmas, that light-glinting time that can illuminate misery as brightly as it does love. Just as in Autumn, art takes centre stage, most literally as our kind-of-protagonist is a man named Art who runs a blog called “Art in Nature”, a meta-pun for both the characters within the story and those of us reading it. Each book in the quartet has printed on the back page a piece of art from the artist that Smith has woven into the story. For Winter it is Barbara Hepworth, whose sculptures reach into the lives of the characters in ways we won’t fully comprehend until Summer. Smith introduces us to Iris, an ageing activist who was as the forefront of the nuclear protests of the 20th century, whose radical outlook provides a warm contrast to the mentions of Trump and our descent into a world politics that seems more and more satirical and terrifyingly real. Art and activism, family and friendship, once again these all go hand in hand as we brave the frost of winter and hope to emerge better.

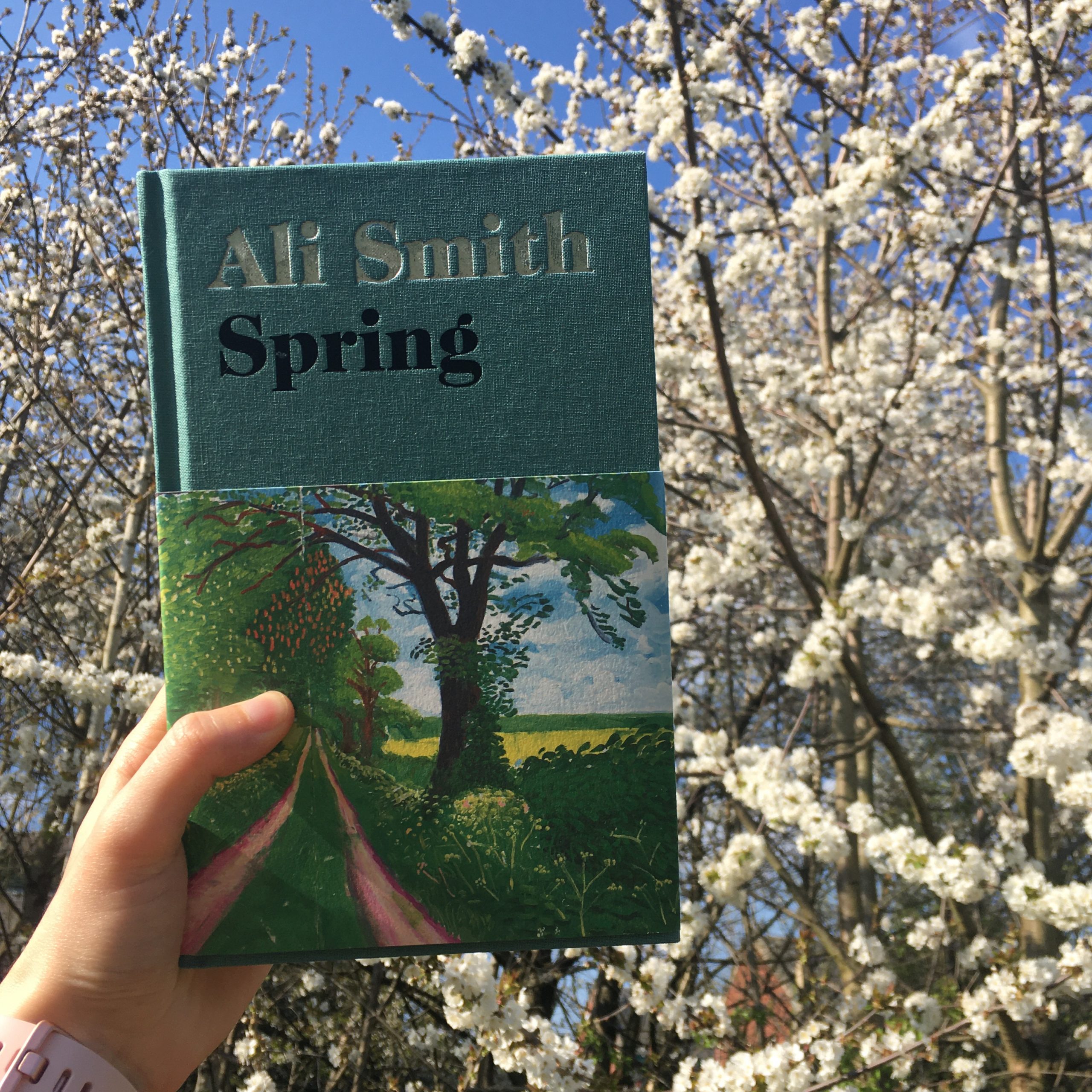

Spring is a far angrier novel, and yet I came out of it empowered, I came out screaming for change and looking for something to do about it. Like the crocuses in March, I was ready for an uprising. A story that pivots around UK immigration detention centres, Spring lays bare the hypocrisy of the UK government and the dehumanisation that people are capable of, especially when it comes to people who look different to us. Once again, Smith considers the duality of humanity. We are capable of locking people up for indefinite amounts of time without having committed any crime, yet we are also capable of risking ourselves to drive the bus to free them. The importance and power of children is, like with the child Elisabeth in Autumn, once again highlighted. Children have a moral compass unaltered by the “logic” of our society, an unencumbered idealism, and an unrivalled imagination. We see this in Florence, the almost magical little girl who simply waltzes into a detention centre and makes the employees improve conditions. All the adults in Spring rally around Florence and see their cynicism melt away as a consequence. This time we are introduced not only to the staple woman artist that each of the quartet studies (this time Tacita Dean), but also a fictional artist/filmmaker through whom we study works of Rilke and Catherine Mansfield. How Ali Smith manages to pack so much art and literature and references and feeling and beauty into such short books I will never understand, but I’m so glad she does. Each of the quartets has a Shakespeare play woven into their narrative, with Spring “riffing on Pericles”. At times the inner monologue of the older man reminded me of that of Margaret Atwood’s Hag-Seed, another book based on a Shakespeare play that is also about people who have been imprisoned, and the hope that art can create.

Sat in the lingering glow of Summer it is easy for me to say “that one was my favourite”, although I’m certain that a re-read of Autumn as the leaves begin to fall will convince me otherwise. Summer pulses with the slow heat of an august haze. The inner mind of a teenage alt-right troll burns, while the coronavirus lockdown lazes across the page, both languid and feverish. Smith manages to capture the summer of 2020 with the kind of accuracy that can only have come from writing inside it, without the over-analysis of hindsight. All the familiar pieces are there, the family dynamics, the surprising friendships, and the subtle study of an artist (Lorenza Mazzetti). Once again Smith weaves together stories from different times, playing with concepts of memory and what “now” means. Summer returns to characters from the previous novels, and we delve into the memory of Daniel from Autumn while he was a young boy in a UK internment camp during WWII. While you can feel the parallel of these camps and the immigration centres, the two experiences are not compared or used as analogies for the other. Instead, the two experiences are presented equally as their own situations, that both share in displaying the fear of “alien enemies” and the capacity for hate that this fear broods. An ex-actress remembers the summer when she performed Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale, a fitting story within a story about the fear of others and Smith finishes Summer, and thus her quartet, with a letter from a man held in an immigration centre, Hero. And I wept.