On the face of it, materialism has never been more prevalent. It manifests itself on social media with everyone from influencers to your circle of friends showing off their latest gift or purchase. As Instagram is labelled as the worst social media platform for our mental health, how do our changing attitudes towards materialism feed into that?

Since the mid-20th century, people have increasingly defined themselves by the material objects they acquire. We build our identities around the clothes, books and food we buy. This phenomenon expands into the experiences we spend money on; holidays, festivals, education. We are just as likely to tag our location to humble brag about a holiday destination as we are to snap a mirror selfie in a new outfit.

Streaming services, e-books and the internet means that splashing out on music, books and magazines is no longer necessary. We are more defined by what we choose to share, than what we choose to buy. Does materialism, often dismissed as self-absorbed vapidity, still have a place in the part of our lives we choose not to share online?

There is definitely something to be said for surrounding yourself with beautiful things, whether you decide to share that online or not. Lifestyle trends from all over the world claim to offer a route to contentment, through the things we do, or do not own. Last year the obsession with Scandanavian lifestyle trend, Hygge, encouraged surrounding yourself with objects that make you feel cozy. This trickled down to candles, blankets and cups of tea; hardly revolutionary given that that is how most Brits already spend their winter evenings, but read an article about the benefits and just try not to be tempted to buy a new woolly jumper or scented candle. Self-care staples, like those at the core of Hygge, allow us to take a step back from what we buy to look cool to others. They give us an experience, no matter how simple that may be.

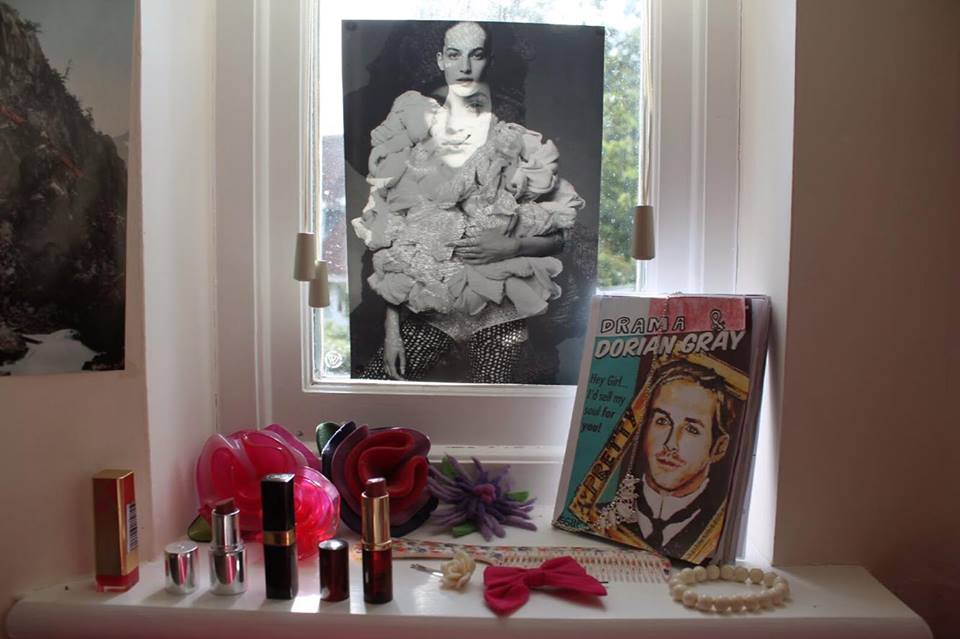

Money can’t buy happiness, but material objects can bring us joy. Mainstream self-care techniques can be reductive in the face of serious mental illness, but a relaxing face mask, cute outfit and your favourite magazine can often help turn your day around. Living between two homes whilst I am at university has made me appreciate the objects I surround myself with. When I am alone, home appears in the form of my favourite books, records and posters. Whenever I feel nervous or uncertain about going somewhere, I take a copy of my favourite book with me.

Materialism is beginning to mean something different. Whilst minimalism is on the rise, even this reflects our fascination with materialism. Minimalists have to be very selective about what they do and don’t buy, so the things they do buy are even more telling. So-called luxury items do not have to be expensive, or create clutter; a candle you love the smell of, a moisturiser that makes you feel more confident, a special copy of your favourite book.

Fashion is inherently materialistic because it relies on defining ourselves by material things. When it comes to clothes, everyone wants to wear something that makes them feel comfortable. In the age of Instagram, our personal style defines us more than ever. Of course, most of us cannot afford designer labels, but we can still appreciate well-made clothes. Vintage stores offer something special for a fraction of the price of a designer alternative, whilst also being a more ethical option than fast fashion. It’s comforting to know that when you put something on in the morning, the money you paid for it did not go towards profitting from sweatshops.

Young people tend to be more conscious of what they are buying now. There are more ethical alternatives to challenge our shopping habits. Picking charity shops over fast fashion, independent cafes over Starbucks, wholefood shops instead of supermarket chains, all says something about us and the way we want to live. Where we buy from is as important as what we buy. Buying is an experience as much as enjoying what we have bought is.

Social media means that our private and public lives are merged more than ever. Our relationship status, birthdays and selfies are out there for the world to see. This leaves a special place for the material things that we keep for ourselves; the incense we burn when we’re alone, cute underwear we put on even when no one is going to see it, and the so-called “guilty pleasures” that we hide from others. On the other hand, if the identity you present to the world is filtered through personal style and that brings you confidence and happiness, then celebrate that too. We are undeniably living in a material world, so where’s the shame in being a material girl?

By Sophie Wilson