Throughout history it can be argued that a woman’s greatest crime is not only having a body, but being self aware of said body; unashamedly walking on this earth admitting that yes, she does have body parts below the neck and above the feet. She has arms, a stomach, boobs, nipples and ohmylord even a vagina.

Now even the most twisted meninist must admit that a women is not merely a floating head, her body does exist. God forbid however, other people notice she has limbs and shit, the thought of this provides that anger that meninists live off.

The world has never liked to admit that women have bodies (of course unless that existence is defined by their bringing of pleasure to men). Some of the most controversially received art has been that which depicted women nude for their own enjoyment, rather than that of the male audience member. Diego Velazquez’s, the leading artist of the Spanish Golden Age, arguably most known and most criticised painting was that of ‘Rokeby Venus,’ completed in 1651. Inspired by Titan’s ‘Venus’, Velazquez’s painting depicts Venus in a sensual pose, lying on a bed and gazing into a mirror held in front of her by the Roman god of physical and erotic love, Cupid. Up until this point all seem innocent, jut a nude goddess, her son and a mirror. However, it is this mirror that becomes that main point of issue as Venus looks into the mirror, yes at the audience, but also at herself. The simple act of her looking at herself rather than aiming all her attention at the male getting off on seeing a nakey ladey.

This happened again in 1865 with the debut of Edouard Manet’s ‘Olympia.’ Another white women, she reclines on her bed as her slave brings her flowers, assumedly from an admirer, which she pointedly ignores. Also modelled after Titan’s Venus, Manet made a point of drawing clear yet contrasting comparisons. In Titan’s painting Venus holds her left hand out in enticement, yet again exciting that male, whereas Manet’s Olympia holds out her left hand appearing to block, which is interpreted as a symbol of her sexual independence – combined with the ignorance of the flowers – from men including that one in the audience. It also acts as a clue to her role as a prostitute; ‘Olympia’ was the name given to prostitutes at the time, which when put alongside the symbolic hand gesture presents her ability to both grant and restrict access to her body, in return for payment, even when nude (take note on consent people). Olympia also gazes out into the audience, as did Venus, and it is this that caused the most shock and horror because of her defiance and lack of shame. She is a woman who uses her body and men for monetary gain and shows no shame at the fact of this. The confrontational gaze of Olympia is often referred to as the pinnacle of defiance towards the patriarchy. Classy high society freaked out.

These were revolutionary paintings in their time, in the sense that there rarely was anything with a similar symbolic meaning in regards to the female body produced and displayed. However, it was a trend in art that continued and evolved over time.

Continuing on into the 20th century with the beginning of the feminist art movement which emerged in the late 1960s as a means of protest and attempt to change the world surrounding women and their bodies, only this time is was through art created by women themselves. As Suzanne Lacey described it, ‘the goal of feminist art was to “influence cultural attitudes and transform stereotypes.” One of the most revered feminist artists of the time was the incredible VALIE EXPORT who’s repertoire includes pieces such as, ‘Tapp- und Tast-Kino’ (Tap and Touch Cinema) 1968-1971 where VALIE wore nothing but a ‘tiny movie theatre’ over her naked body. She visited various European cities, inviting onlookers, unable to actually see her body, to reach through the curtain and touch her. So great was the horrified reaction to this piece that one media outlet aligned her to a witch. In 1968 in her performance, ‘Aktionshose: Genitalpanik’ (Action Pants: Genital Panic), she entered an art cinema in Munich, wearing crotchless pants and walked through the audience with her exposed genitalia at face level with the aim to provoke thought surrounding the passive role of women in cinema and confrontation of the private nature of sexuality with the public nature of her performances.

In her performances, the female body is not a packaged, perfect product sold by males (in the form of directors and producers), but is controlled and offered freely by the woman herself in defiance of social rules and state precepts, similar to that of Manet’s Olympia’s role as a prostitute and her granting and withholding of her body as she so chooses. EXPORT’s cinema performance also contrasts the ordinary state-approved cinema, an essential voyeuristic experience similar in that to the old nude painting of women in a gallery. As in her piece the “audience” not only has a very direct and tactile contact with an exposed female body, but does so under the gaze of EXPORT herself and all other bystanders. She exposes both herself and the audience through her chosen nudity. The later horror of the “civilised” individual then exposes societal prejudice to the female form and the women who utilise it.

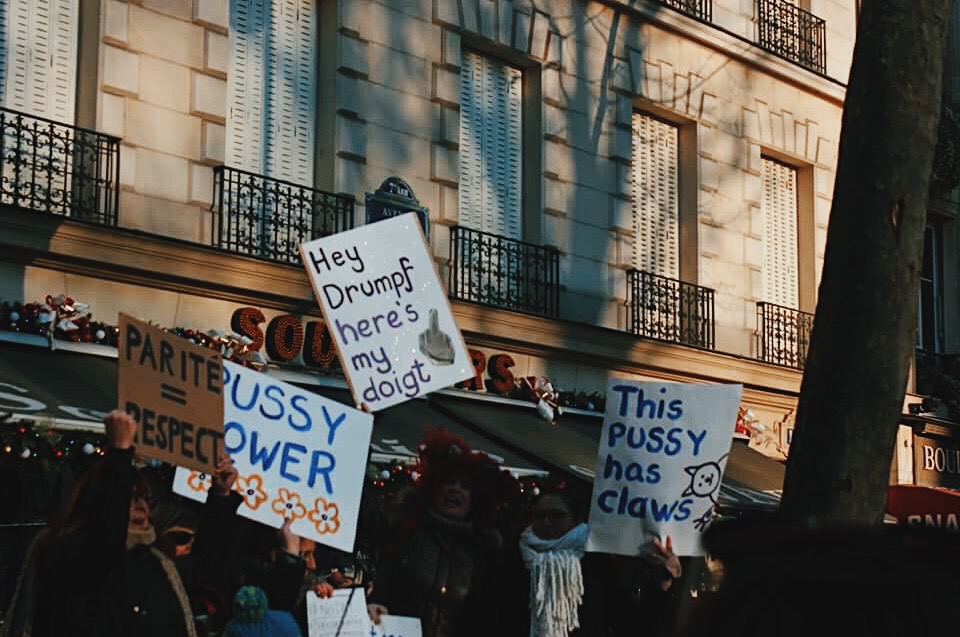

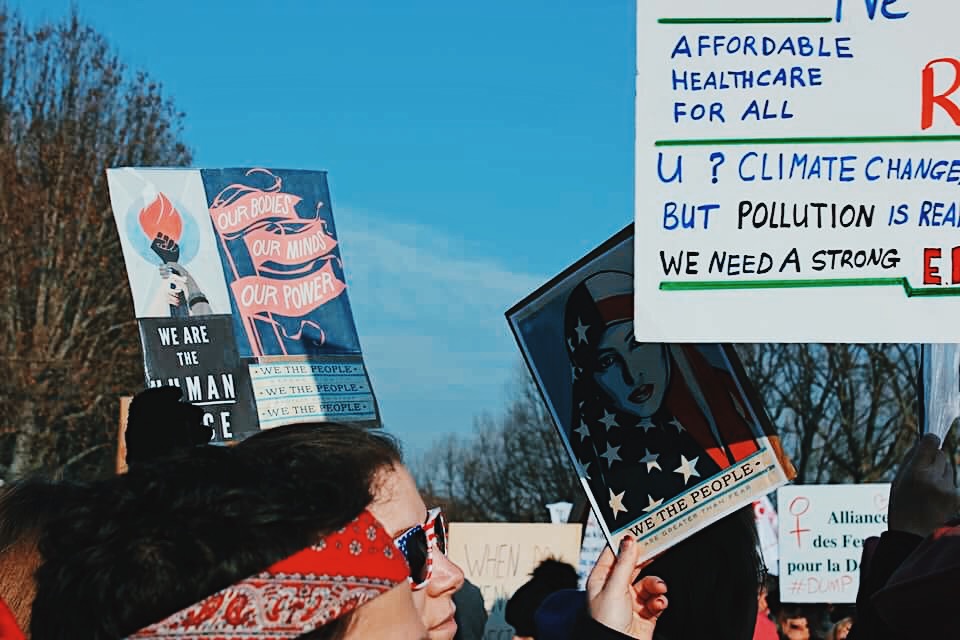

Now, around 50 years later, many of the artists of the past’s points and aims have filtered into society and the work of the modern day average feminist. From “glow up” #bodyposi and #feelinmyelf, which see women (and men also) celebrating their own bodies publicly through their own choice of photo, platform etc and sharing this pride with the world, to the new slut marches of LA which loudly confront the continued association of free women and derogetary terms in eyes of society. The art of the past has both inspired and allowed women to reach a point where, with the help of the internet and social media, we can challenge the world view and stereotypes with our own bodies and voices. We can make our own oil paintings in the photos on our phone and political art through mass protests and emerging trend of spoken word poetry. This ability and trend is also reaching into deeper feminist issues facing those of women of colour and the lgbt+ community as they also explore their own bodies and push the old and outdated boundaries of societal beauty and grace, constantly challenging the audience (other social media users) to question their reactions and their views and better themselves as a result.

As women we grow to learn how our bodies have always been and continue to be political battlegrounds for us to fight for and watch (most often men) fight over. It is through art and the modern day ability to control the world view of our own bodies that we begin to regain this battleground as one we can enter and exit when we choose and this is something that must continue to be fought for as we help bring other women up with us and prevent us being dragged back into the dark past of male control. I’m looking at you Trump.

(this article is written from the perspective of a white cis women and therefore is restricted in it’s experiences of women of colour and trans women and details of the struggles surrounding their bodies, mostly through a lack of wanting to speak for those groups or offer opinion/ perceived history of their struggles from the view point of a white cis person.)

By Eliza Caraher