(Psst. Allegory – a story, poem, or picture that can be interpreted to reveal a hidden meaning, typically a moral or political one.)

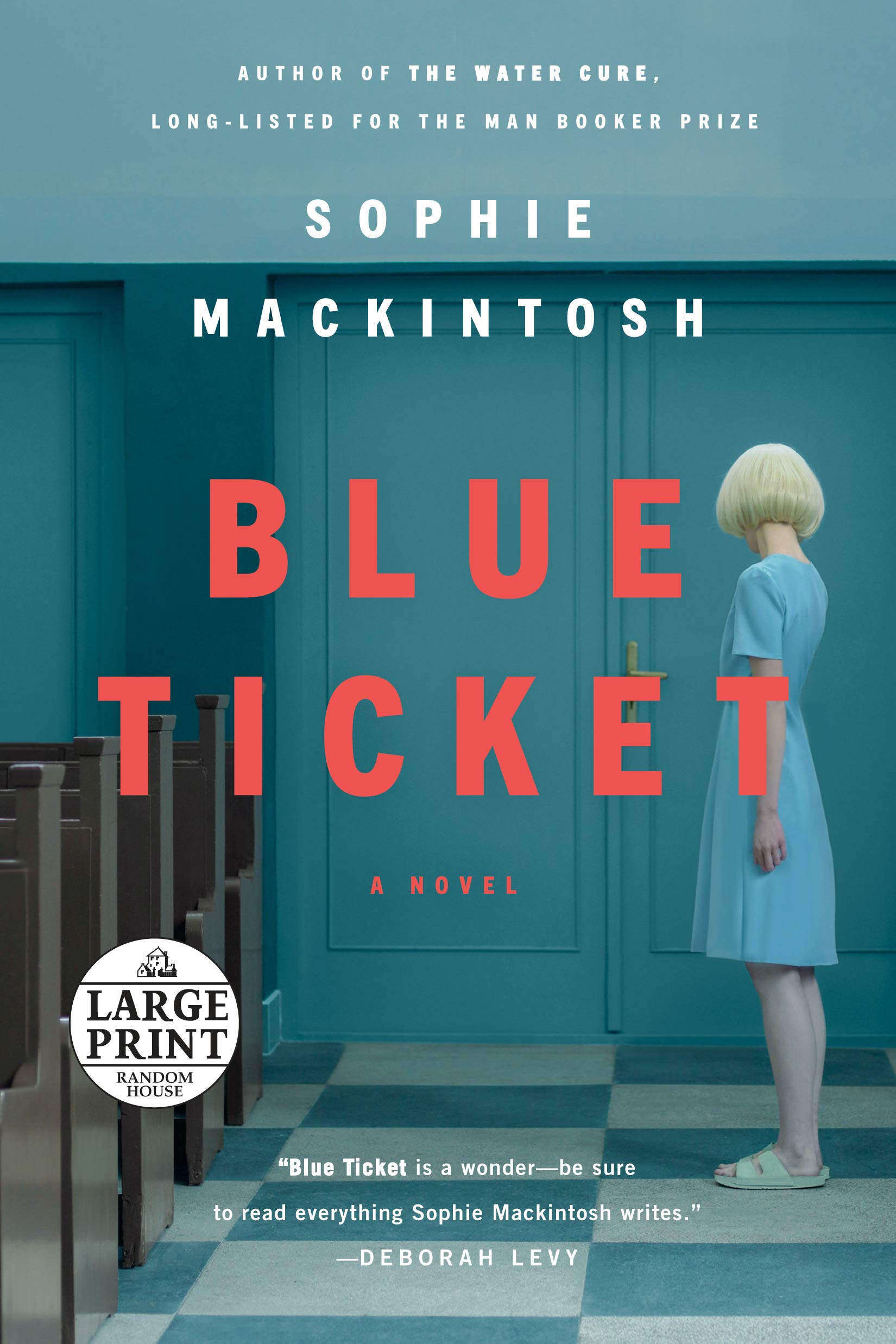

Blue Ticket – Sophie Mackintosh

It was pretty much decided after being pulled full-force into her lulling dystopian debut novel, The Water Cure, that I was going to read everything Sophie Mackintosh ever writes. So, I pre-ordered Blue Ticket the moment it was possible and waited impatiently for it to arrive on my doormat. With such high expectations, disappointment would have been easy. Luckily, Mackintosh has proven that she has more than one story in her, and I’d guess she has many more still to come.

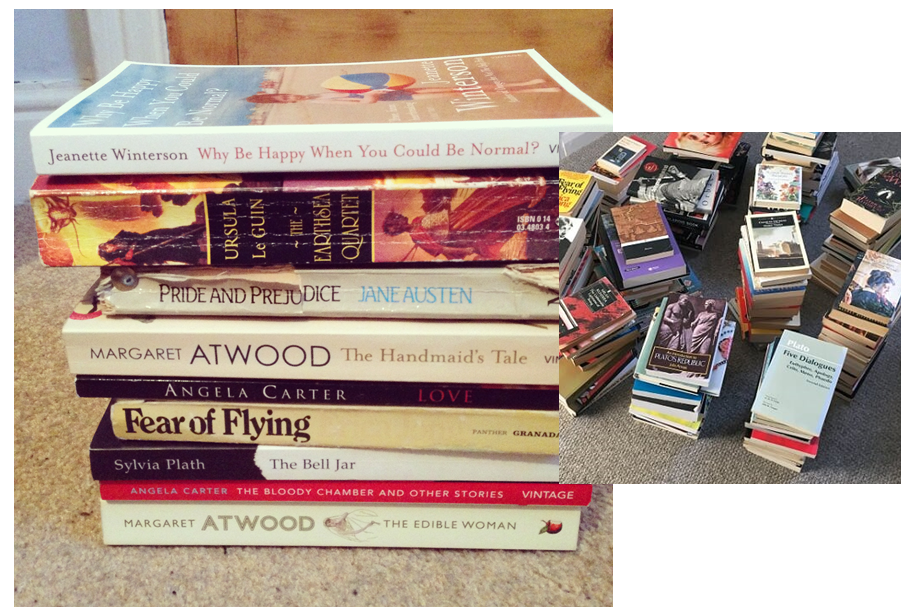

A few pages into Blue ticket, I began to worry that this patriarch-fascist dystopia based on the policing and enforcing of reproduction veered too close to Handmaid’s Tale territory, by no means a book comparison to be scoffed at, yet to be derivative of something good is still to be derivative. By the time the book was in full swing, however, and its surreal dream-like substance came into full colour, there was no doubting its originality. Somehow fantastical without becoming magical, Blue Ticket feels like a fairy-tale without the fairies. It is soft and hard all at once, like standing on broken glass in fuzzy slippers.

Sophie Mackintosh has solidified her position as queen of the allegory of female embodiment, emphasising and transforming the lived experience of those who occupy the space called ‘woman’ and the expectations and limitations it comes with. In Blue Ticket the decision to have children is taken away, and you are “free” of the burden of choice, being assigned a blue or white ticket, a childless life or a life as a mother. At first, we see how maybe this removal of choice could be liberating, freeing us from the weight of regret at making the wrong choice. But what happens if everything in you is telling you to make the opposite choice to the one you were assigned? Control is never the way to liberation and women are only free when they are truly free to choose. I found it interesting that our protagonist was a blue ticket woman becoming pregnant illegally, when so often the discussion about women’s right to choose centre the desire to not have children. I also felt that this was especially poignant after recent revelations of forced sterilisations and the rise of thinly veiled racist eco-fascism. The right to reproduce must be fought for as voraciously as the right to not.

Blue Ticket also captures the unsettling anxiety that comes from not knowing what your body is doing, a real life worry of people born in female bodies exaggerated. The blue ticket women are not told about the physical changes that pregnant people experience, and thus each new change is a terror. This is not so different to the real-life experience of those who inhabit a female body in a society which has neglected the study of female pain, pregnancy, sexuality and embodiment. To be born female is to inhabit a body which “at once [feels] distant as the moon and uncontrollably close”, alien and inescapable. And when it comes to pregnancy, alien is the word. Mackintosh describes pregnancy with brutal honesty, laying bare its strangeness and the havoc it rages through the body; the most natural animalistic process, rendered sci-fi by our lack of knowledge. I have never read an account of pregnancy that so viscerally displays the shock of oneself becoming two-selves, shying neither from the horror nor the tenderness.

By far my favourite section was “Cabin”. Pregnant women bathing each other in rusted tubs with water boiled on a stove, a circle of women fleeing from the state and setting up commune in a cabin in the woods as vines creep their way through the windows, fucking and scavenging and trying to survive: a feral cottage-core dream, like something from an Angela Carter tale. Reading this section was like being in a cinema, so vivid was its imagery, and cinematic its sparse tone. Mackintosh shows you rather than tells you the story and I experienced it in the muted pastel shades and de-saturated muddy browns of an early 2000s Sofia Coppola film.

The Illness Lesson – Clare Beams

I stumbled across Clare Beams’ debut novel in a bookshop display. The textured cover art, replicating embroidery, caught my eye, as did its title. As a chronically ill woman, I am drawn to books about illness in general, and especially ones by women. A quick scan of the blurb: “mysterious flock of birds…philosopher…school for young women…bizarre symptoms…confront the all-male, all-knowing authorities or her world, who insist the voices of the sufferers are unreliable”, and I was sold.

The Illness Lesson begins in the fashion of contemporary fiction of the era in which it is set, perhaps of the ilk of Louisa Alcott’s Little Women, who Beams writes in her Acknowledgements to have been an inspiration for the book. Set in 1871, Beams situates the novel only a few years after Little Women finished. Quickly, however, it becomes apparent that this novel is more akin to the gothic fiction of that era, than to the romantic. The terror unfolds slowly, gathering speed, injecting small anxious moments, then bringing it back, and again, and again, until there is no escaping the horrors as the book reaches its terrifying crescendo. This building pace lends The Illness Lesson a feel of the later classic gothic horrors like Shirley Jackson’s Haunting of Hill House and the same page turning grip.

Our protagonist, Caroline, is the daughter of a famous philosopher who decides to open a school for young girls to prove that they are every bit as capable as boys. A heavy dread lies over the schools opening, thanks to the arrival of a flock of red birds, which to Caroline appear to be a mystical bad omen, and mentions of a famous ghost story written about the house in which they are to open. As the girls’ lessons progress, the birds begin to build nests, and the girls begin to develop mysterious physical symptoms. Dismissing these symptoms, the teachers of the school believe that the girls have willed themselves ill. The conversations which follow are depressingly familiar: “she’s saying there’s something wrong…wouldn’t she know?”… “you want me to pretend this isn’t happening?”… “but an ill girl – it isn’t so unusual. Everyone knows one.”. To treat the girls, the men ignore the protestations of the two women teachers and bring in another man to administer the same traumatic treatment that thousands of women who had been diagnosed with ‘hysteria’ suffered often in our not-so-distant past.

The Illness Lesson shows how it is possible that medical negligence and sexual assault have taken place so brazenly for centuries. The dismissal of female pain and the removal of agency results in lack of scientific knowledge of the female body, which in turn lends mystery to the ailments it suffers, further fuelling the idea that is it unpredictable and untrustworthy, and needing to be controlled. The same ideas and structures which uphold medical sexism also underpin rape culture. Ultimately, if we don’t trust what women say about their own bodies, their bodies become playgrounds for the whims of men. This failure results not only in trauma being inflicted upon the female body, but in its inhabitants feeling lost within their own skin and doubtful of their own experience, perfectly encapsulated in the sentence “she did not trust her voice or the body it came from”.

Therein lies the beauty of The Illness Lesson: The ominous birds, the ghost story. This novel feels at times like magical realism to be placed alongside Toni Morrison or Angela Carter, and at others like a gothic horror at home amongst Shirley Jackson and Mary Shelley, still others it is reminiscent of the feminist dystopias of Margaret Atwood and Sophie Mackintosh. Yet, the true horror is not magic, ghosts, or a reimagined world, it is the reality of our recent past, and the legacy it has left us with today. The birds, a literal red herring; the monsters, men; the dystopia, reality.